Leading with Character: Mentoring Misperception #1

“You must look beyond what you can see and dream of, then reach for, what you imagine.”

Mentoring—both giving and receiving—helped me achieve my career and personal goals. If done properly, avoiding the following three misperceptions, mentoring can have a positive impact all around. This week I’ll address mentoring misperception #1.

Mentoring Misperceptions

- Mentors must look like you

- Mentors must be senior to you

- A mentor will make you successful

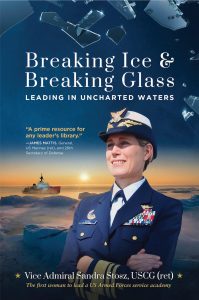

None of my mentors looked like me. Entering the Coast Guard Academy with the third class to include women, I was often the only woman leading mostly all-male teams throughout my career. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have been mentored by men dedicated to helping me advance and succeed.

A misperception has surfaced that people cannot succeed in an organization unless they see someone above who looks like them. I don’t subscribe to the “you’ve got to see one to be one” myth. It’s self-defeating. My experience has taught me that people limit themselves more than they are limited by others. You must look beyond what you can see and dream of, then reach for, what you imagine.

Certainly, organizations should include people at every level who reflect the diverse society they serve. That does not mean members should exclusively seek mentors who look like them or mistakenly believe a mentor who looks like them will assure their success.

On the contrary, those who desire to lead and succeed in ever more diverse organizations should actively seek people who don’t look like them. They will glean a valuable perspective and expand their network. Diversity is all about different perspectives. Individuals who surround themselves with people who look and think the same will restrict their professional development.

One of the best mentors I ever had was Secretary of Transportation Sam Skinner. When I served as his military aide from 1989-1990, he taught me lifelong lessons on leadership and one of its core components—followership. Dedicated to providing opportunities to top performing women and minorities, Secretary Skinner created a highly visible job to enhance my professional development. I accompanied him to his meetings and events, ensuring any action items arising out of those engagements were completed.

I will never forget the secretary’s first gathering of all the modal administrators, which occurred early in his administration. The modal administrators were the transportation agency heads—the senior-most leaders in the department. They consisted of the Coast Guard commandant, along with the heads of the other transportation modes, including the Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Highway Administration and Federal Railway Administration.

The new senior leadership team was still forming. People did not yet know each other well and most weren’t accustomed to their roles. During the introduction phase of this inaugural meeting, the secretary looked at me, the only junior person in the room and stated, “This is Lieutenant Stosz, my military aide. She will attend all my meetings and follow up directly with you on action items. When she speaks, you’ll listen, because she’s speaking for me.”

I sunk a little lower in my chair as the eyes of the commandant of the Coast Guard fixed icily upon me, conveying the warning, “We’ll see about that!”

The other modal administrators, civilians accustomed to working with younger people in responsible positions, thought nothing of the secretary’s proclamation. Shortly after the meeting, I discovered I’d already been fondly christened with a new nickname, “Lieutenant Follow-Up.” The moniker stuck and followed me for years afterward.

Although Secretary Skinner empowered me with significant responsibility and ensured I had the necessary authority, I started out as an unknown quantity to the senior leadership team. I quickly learned the secretary’s confidence in me wasn’t enough. I needed to build trust with and earn the respect of the senior leaders. Being a good follower meant I had to learn how each modal administrator operated and adapt to get my job done. Most of the modal administrators mentored me in navigating the department and understanding politics.

By trusting me with such significant responsibility, Secretary Skinner won my intense loyalty and undying respect. I didn’t want to let him down or fail him in any way and gladly put in the demanding hours the job required. In addition to trusting me, Secretary Skinner truly believed in me and recognized my potential even when I did not.

Long after being reassigned to my next position, Secretary Skinner continued to mentor me. He flew to Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, to preside at the ceremony when I assumed command of the cutter Katmai Bay. Later, he wrote a letter of recommendation supporting my application to the Kellogg Business School. And, in keeping with his commitment to lifelong mentoring, he flew to Washington, DC to share in my retirement ceremony nearly thirty years after my assignment as his military aide.

Look in the mirror. Are your mentors and/or mentees just like you, or are you seeking diverse perspectives?

Please join me again next week for more on Leading with Character.

Delegating responsibility requires courage because it involves risk taking on the part of the mentor. Good leaders take risks to encourage, guide, and provide cover for their people. A good organization insists its leaders develop the workforce, even if there is no personal benefit to the leader. There is no room for risk aversion in real leadership.